Thu, Nov 20, 9:51 am | UCSB Reads

For its 20th anniversary year, UCSB Reads selects a provocative book about identity, food, grief, and culture

The UC Santa Barbara Library and the Office of the Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost are pleased to announce the selection of Crying in H Mart: A Memoir (2021) by Michelle Zauner for...

Wed, Nov 19, 12:18 pm | Library Employees, UCSB Reads

UCSB Library received five awards in 2025 in recognition of its outstanding communications:

ARL 2025 ARLIES Award

The Association of Research Libraries (ARL) awarded the 2025 ARLIES Award for Best Publicity/Marketing Film for the "Gen Z-Scripted Tour of UCSB Library" video at the ARL Spring...

Fri, Nov 7, 12:54 pm | Gifts & Donors, Special Research Collections

This is a slightly edited version of an article that was first published in UC Santa Barbara's The Current.

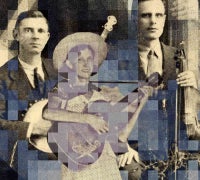

Thousands of songs representing some of the rarest and most uniquely American music borne from the Jazz Age and the Great Depression would have likely been lost to landfills and faded from...

Thu, Nov 6, 11:17 am | Gifts & Donors, Special Research Collections

UC Santa Barbara Library is celebrating the preservation and digitization of the KEYT Television Archive, a collection documenting more than 60 years of Santa Barbara history and community journalism.

Donated to the Library in 2016, the archive includes over 2,700 videotapes and millions of feet of...

The Makerspace is a free, creative resource within the UCSB Library available to all students, faculty, and staff. We offer access to technology including 3D printing, laser cutting, sewing, electronics prototyping, and more.

For many students, a writing class conjures images of textbooks, lectures...

In celebration of Open Access Week 2025 (October 20-26), the UCSB Library spoke with Kate McDonald, Associate Professor in the History Department, about publishing her book Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan open access.

The UCSB Library is committed to...

Mon, Sep 15, 8:49 am | Gifts & Donors, Special Research Collections

The creative vision behind cinematic landmarks like The Fugitive, Under Siege, and Holes has found a permanent home at UC Santa Barbara. UCSB Library is honored to announce the acquisition of the archives of acclaimed filmmaker Andrew Davis, a major addition to its growing Film & Television...

OCT. 24, 2025, UPDATE: For the remainder of the 2025-2026 Academic Year, UCSB Library will open to the public at 7:00 AM Monday-Friday and remain open to UCSB students, faculty, and staff from 1:00 AM to 3:00 AM on Sunday-Thursday nights for Study Commons. View building hours.

In response to...

The Makerspace is a free, creative resource within the UCSB Library available to all students, faculty, and staff. We offer access to technology including 3D printing, laser cutting, sewing, electronics prototyping, and more.

Professor Annie Lamar, who directs the Low-Resource Language (LOREL) Lab...

Thu, Aug 7, 9:28 am |

The UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) Library has received a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) to preserve and digitize Don’t Bank on Amerika (1970), a documentary capturing a pivotal moment in the history of student activism at UCSB and across the nation.

Filmed by cultural critic...